[This chapter of the story contains almost exclusively extended quotes from Mayer and Blight, biographers of Garrison and Douglass.]

The “Preliminary Proclamation”

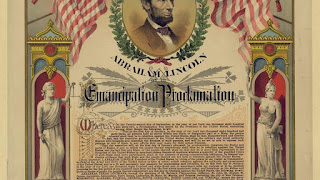

President Abraham Lincoln announced on September 22, 1862 "That on the first day of January .. 1863, all persons held as slaves within any State ... in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward and forever, free…” His apparent goal was to bring the rebel states back into the Union, and the preliminary proclamation left many questions unanswered and contained provisions under several different scenarios. Thus, Americans with direct interest in the question waited for the outcome 100 days hence ...

"The moment might well be delayed, for the prefatory clause of the president’s message promised that he would renew his request that Congress appropriate money for a voluntary and gradual compensated emancipation in the border states. The moment might not last, for the very same clause also promised a continuation of the administration’s effort to “colonize persons of African descent, with their consent,” in some other country. The moment might not come at all if the South accepted the offer to give up the war and keep its slaves. Was the president’s proclamation a promise or an ultimatum, a giant’s stride or a pygmy’s step, the realization of a dream or the continuation of an ambiguous voyage whose outcome remained uncertain? (Mayer, 542)

William Lloyd Garrison, the ideological leader of the abolitionist movement .. "didn’t know, which is why a visitor hurrying to congratulate the pioneer found him curiously subdued, worrying over the text, and distinctly lacking in enthusiasm. Of course it was an act of “immense historic significance,” and the people who were rejoicing, he said, were justified “as far as it goes.” He could not be jubilant, however, when “what was wanted, what is still needed, is a proclamation, distinctly announcing the total abolition of slavery.” (Mayer, 542)

"In the fall congressional elections of 1862, the Democrats made sweeping gains; Republicans suffered at the polls because of emancipation, and a “depressed” Lincoln, as numerous biographers have suggested, did not know quite where to turn… In the anxious hundred days between the Preliminary and final Emancipation Proclamations, jubilation gave way to confusion in abolitionist and free-black communities. (Blight, 380)

"For Frederick Douglass, his family, and the entire abolitionist community, the fall of 1862 was a sleepless watch night that lasted three months. “The next two months,” Douglass wrote in November, “must be regarded as more critical and dangerous than any similar period during the slaveholder’s rebellion.” The “apprehension,” he said, felt “far more political than military.” Douglass threw himself into the election fray as a partisan Republican. (Blight, 380)

"Douglass also kept up a fervent correspondence about emancipation and a fund-raising campaign with his British friends… In October Douglass wrote a public letter to his British and Irish friends, in which he gushed with new hope for the cause, gratitude for past financial and moral resources, and made an aggressive appeal for more money. Douglass became a one-man political-action committee for emancipation. He expressed special thanks for all the support over the years for the Underground Railroad, but as of September 22, he remarked, its “agents” were “out of employment.” With Lincoln’s Proclamation, Douglass assured his foreign readers, America had started the “first chapter of a new history.” Now was the time for continued aid, said the editor with bills to pay and a thrilling new revolution to lead. The end is not yet,” he cautioned. “We are at best only at the beginning of the end.” The following month, Douglass the cheerleader proclaimed the Preliminary Proclamation the nation’s “moral bombshell” shaking everything into new forms. (Blight, 381)

(At the close of December, as uncertainty characterized the movement in light of the past three months of discussion, negotiation, and alternative proposals, even from Lincoln himself …) "Sumner passed the word that Lincoln had told him personally that he would not stop the proclamation if he could and that he could not if he would. Garrison, however, remained skeptical until the very end.” (Mayer, 544)

January 1, 1863

(On that day) "no one knew quite what to expect. No text had come in advance from Washington for the morning papers. Would word perhaps arrive at noon, after the president had communicated with Congress? … The entire Garrison family prepared to attend an afternoon Jubilee concert at the Music Hall, sponsored by a committee of distinguished literary figures headed by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Francis Parkman, and Oliver Wendell Homes, that would raise money for the contraband relief effort. (Mayer, 545)

"This was a society gathering – of the people of property and standing, who had come so slowly and grudgingly to abolitionism that it seemed not quite the right place for (Garrison) to be at the anticipated moment of triumph. Yet Garrison elected to attend, though William C. Nell had invited him to a meeting going on simultaneously at Tremont Temple sponsored by a black political association at which John S. Rock and Frederick Douglass were to speak. The editor had turned him down, Nell said, “for reasons satisfactory to himself.” But which no one ever disclosed… It is tempting to posit lingering ill will with Douglass as a reason to hand back, but it is just as easy to suggest that Garrison did not want to crowd (or be charged with crowding) Douglass on a day that surely belonged to him as much as anyone. (Mayer, 545)

(The lengthy program included speeches, poetry, choral symphony. Late in the program, Ralph Waldo Emerson offered an original poem for the occasion, “Boston Hymn.” The music resumed…) “Mendelssohn’s “Hymn of Praise” thrilled its listeners with this plaintive question “Watchman, will the night soon pass?” and the stirring choral response “The night is departing, the day is approaching.” The audience sat attentively through a Beethoven piano concerto, but milled about restlessly in the interval that followed. No word had come from Washington. (Mayer, 546)

"Holmes had just finished reading several additional stanzas of poetry when Quincy rushed to the platform with the joyous news. The president had just signed the proclamation! The text would be coming over the wire later in the evening. The Music Hall erupted in pandemonium, with a shouting and screaming and crying and roaring that the staid assembly had never in its life experienced. … The cacophony in the hall became a chorus of its own. “Three times three for Lincoln” went the call, and the floor shook as people stamped their feet and nine great shouts welled up from three thousand voices all at once. “Three cheers for GARRISON!” someone else yelled. Suddenly every head turned to find the editor, who leaned out over the latticed gallery wall to wave and smile. The cheers burst into the air for the backstreet Baptist boy who had flung his words into the whirlwind and survived a Boston mob to print and preach and call from the depths of his prophetic soul this hour into life. (Mayer, 546)

"Beginning at 10:00 a.m., a largely black-organized meeting assembled throughout the day, reaching approximately three thousand people, at the magnificent Tremont Temple. Presided over in the early hours by black Garrisonians William Cooper Nell and Charles Lenox Ramond, the speeches, poetry, and singing were confidently joyous. (Blight, 382)

"Douglass was the final speaker at the afternoon session. He alluded with irony to the two years earlier when he and others had been driven from that same stage by a mob prepared to kill abolitionists. He honored the slaves of the South for their forbearance in not rising in insurrection and appealed for what he hoped would be the imminent enlistment of black men in he Union armies. On behalf of the abolitionists he boasted that their warning delivered for decades was now coming to fruition in the “blood” of the moment, as he also predicted much more blood to come. Douglass soared, assuring the audience they had lived through a “period of darkness” into the “dawn of light.” (Blight, 382)

Tremont Temple Baptist Church, photo taken August 2019

"After a break, the huge crowd grew even larger for the nighttime celebration and the anticipated news of Lincoln’s signing the Final Proclamation. But a mood of anxiety and doubt set in throughout the hall as the evening hours crept by without the word. The organizers maintained a group of runners to and from the telegraph office in downtown Boston. They all awaited, as Douglass remembered, “the first flash of the electric wires.” Their emotions danced between hope and fear. Would Lincoln indeed sing the wonderful decree? Would it be altered? Would there be some last-minute compromise in Washington or even with the Confederacy? Rumor and experienced pushed back constantly against analysis and biblical expectation of the Jubilee…”Every moment of waiting chilled our hopes,” Douglass recalled years later. “Eight, nine, ten o’clock came and went, and still no word.” With a “visible shadow” falling over the crowd, Douglass said, a man finally stepped hastily through the crowd and shouted, “It is coming! It is on the wires.” He was immediately followed by someone who tried to read some portion of the text of the Emancipation Proclamation, but was quickly drowned out by shouting and a “scene … wild and grand.” In the next hour Douglass hugged perhaps more people than he had before in his entire life, some of whom were old enemies. That night there were no Garrisonian or anti-Garrisonian tears. An old preacher named Rue stood front and center with Douglass as they led the assembled in the anthem “Blow Ye the Trumpet, Blow” and repeated the verse “Sound the loud timbrel o’er Egypt’s dark sea, / Jehovah hath triumphed, his people are free.” (Blight, 383)

"Early the next morning Garrison rushed to The Liberator’s office. The proclamation was better than expected. It did more than free the confiscated slaves of rebels; it emancipated all the slaves in the rebel states. Not only would the nation regard all those people as free, but it would extend military protection to them and accept their enlistment “in the armed service of the United States.” … Lincoln’s eloquence flared momentarily in the concluding lines describing the decree as “an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity” for which he asked “the considerate judgement of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.” (Mayer 547)

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blight, D. W. (2018). Frederick Douglass. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Mayer, H. (1998). All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation/transcript.html

The “Preliminary Proclamation”

President Abraham Lincoln announced on September 22, 1862 "That on the first day of January .. 1863, all persons held as slaves within any State ... in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward and forever, free…” His apparent goal was to bring the rebel states back into the Union, and the preliminary proclamation left many questions unanswered and contained provisions under several different scenarios. Thus, Americans with direct interest in the question waited for the outcome 100 days hence ...

"The moment might well be delayed, for the prefatory clause of the president’s message promised that he would renew his request that Congress appropriate money for a voluntary and gradual compensated emancipation in the border states. The moment might not last, for the very same clause also promised a continuation of the administration’s effort to “colonize persons of African descent, with their consent,” in some other country. The moment might not come at all if the South accepted the offer to give up the war and keep its slaves. Was the president’s proclamation a promise or an ultimatum, a giant’s stride or a pygmy’s step, the realization of a dream or the continuation of an ambiguous voyage whose outcome remained uncertain? (Mayer, 542)

William Lloyd Garrison, the ideological leader of the abolitionist movement .. "didn’t know, which is why a visitor hurrying to congratulate the pioneer found him curiously subdued, worrying over the text, and distinctly lacking in enthusiasm. Of course it was an act of “immense historic significance,” and the people who were rejoicing, he said, were justified “as far as it goes.” He could not be jubilant, however, when “what was wanted, what is still needed, is a proclamation, distinctly announcing the total abolition of slavery.” (Mayer, 542)

"In the fall congressional elections of 1862, the Democrats made sweeping gains; Republicans suffered at the polls because of emancipation, and a “depressed” Lincoln, as numerous biographers have suggested, did not know quite where to turn… In the anxious hundred days between the Preliminary and final Emancipation Proclamations, jubilation gave way to confusion in abolitionist and free-black communities. (Blight, 380)

"For Frederick Douglass, his family, and the entire abolitionist community, the fall of 1862 was a sleepless watch night that lasted three months. “The next two months,” Douglass wrote in November, “must be regarded as more critical and dangerous than any similar period during the slaveholder’s rebellion.” The “apprehension,” he said, felt “far more political than military.” Douglass threw himself into the election fray as a partisan Republican. (Blight, 380)

"Douglass also kept up a fervent correspondence about emancipation and a fund-raising campaign with his British friends… In October Douglass wrote a public letter to his British and Irish friends, in which he gushed with new hope for the cause, gratitude for past financial and moral resources, and made an aggressive appeal for more money. Douglass became a one-man political-action committee for emancipation. He expressed special thanks for all the support over the years for the Underground Railroad, but as of September 22, he remarked, its “agents” were “out of employment.” With Lincoln’s Proclamation, Douglass assured his foreign readers, America had started the “first chapter of a new history.” Now was the time for continued aid, said the editor with bills to pay and a thrilling new revolution to lead. The end is not yet,” he cautioned. “We are at best only at the beginning of the end.” The following month, Douglass the cheerleader proclaimed the Preliminary Proclamation the nation’s “moral bombshell” shaking everything into new forms. (Blight, 381)

(At the close of December, as uncertainty characterized the movement in light of the past three months of discussion, negotiation, and alternative proposals, even from Lincoln himself …) "Sumner passed the word that Lincoln had told him personally that he would not stop the proclamation if he could and that he could not if he would. Garrison, however, remained skeptical until the very end.” (Mayer, 544)

January 1, 1863

(On that day) "no one knew quite what to expect. No text had come in advance from Washington for the morning papers. Would word perhaps arrive at noon, after the president had communicated with Congress? … The entire Garrison family prepared to attend an afternoon Jubilee concert at the Music Hall, sponsored by a committee of distinguished literary figures headed by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Francis Parkman, and Oliver Wendell Homes, that would raise money for the contraband relief effort. (Mayer, 545)

"This was a society gathering – of the people of property and standing, who had come so slowly and grudgingly to abolitionism that it seemed not quite the right place for (Garrison) to be at the anticipated moment of triumph. Yet Garrison elected to attend, though William C. Nell had invited him to a meeting going on simultaneously at Tremont Temple sponsored by a black political association at which John S. Rock and Frederick Douglass were to speak. The editor had turned him down, Nell said, “for reasons satisfactory to himself.” But which no one ever disclosed… It is tempting to posit lingering ill will with Douglass as a reason to hand back, but it is just as easy to suggest that Garrison did not want to crowd (or be charged with crowding) Douglass on a day that surely belonged to him as much as anyone. (Mayer, 545)

(The lengthy program included speeches, poetry, choral symphony. Late in the program, Ralph Waldo Emerson offered an original poem for the occasion, “Boston Hymn.” The music resumed…) “Mendelssohn’s “Hymn of Praise” thrilled its listeners with this plaintive question “Watchman, will the night soon pass?” and the stirring choral response “The night is departing, the day is approaching.” The audience sat attentively through a Beethoven piano concerto, but milled about restlessly in the interval that followed. No word had come from Washington. (Mayer, 546)

"Holmes had just finished reading several additional stanzas of poetry when Quincy rushed to the platform with the joyous news. The president had just signed the proclamation! The text would be coming over the wire later in the evening. The Music Hall erupted in pandemonium, with a shouting and screaming and crying and roaring that the staid assembly had never in its life experienced. … The cacophony in the hall became a chorus of its own. “Three times three for Lincoln” went the call, and the floor shook as people stamped their feet and nine great shouts welled up from three thousand voices all at once. “Three cheers for GARRISON!” someone else yelled. Suddenly every head turned to find the editor, who leaned out over the latticed gallery wall to wave and smile. The cheers burst into the air for the backstreet Baptist boy who had flung his words into the whirlwind and survived a Boston mob to print and preach and call from the depths of his prophetic soul this hour into life. (Mayer, 546)

"Beginning at 10:00 a.m., a largely black-organized meeting assembled throughout the day, reaching approximately three thousand people, at the magnificent Tremont Temple. Presided over in the early hours by black Garrisonians William Cooper Nell and Charles Lenox Ramond, the speeches, poetry, and singing were confidently joyous. (Blight, 382)

"Douglass was the final speaker at the afternoon session. He alluded with irony to the two years earlier when he and others had been driven from that same stage by a mob prepared to kill abolitionists. He honored the slaves of the South for their forbearance in not rising in insurrection and appealed for what he hoped would be the imminent enlistment of black men in he Union armies. On behalf of the abolitionists he boasted that their warning delivered for decades was now coming to fruition in the “blood” of the moment, as he also predicted much more blood to come. Douglass soared, assuring the audience they had lived through a “period of darkness” into the “dawn of light.” (Blight, 382)

Tremont Temple Baptist Church, photo taken August 2019

"After a break, the huge crowd grew even larger for the nighttime celebration and the anticipated news of Lincoln’s signing the Final Proclamation. But a mood of anxiety and doubt set in throughout the hall as the evening hours crept by without the word. The organizers maintained a group of runners to and from the telegraph office in downtown Boston. They all awaited, as Douglass remembered, “the first flash of the electric wires.” Their emotions danced between hope and fear. Would Lincoln indeed sing the wonderful decree? Would it be altered? Would there be some last-minute compromise in Washington or even with the Confederacy? Rumor and experienced pushed back constantly against analysis and biblical expectation of the Jubilee…”Every moment of waiting chilled our hopes,” Douglass recalled years later. “Eight, nine, ten o’clock came and went, and still no word.” With a “visible shadow” falling over the crowd, Douglass said, a man finally stepped hastily through the crowd and shouted, “It is coming! It is on the wires.” He was immediately followed by someone who tried to read some portion of the text of the Emancipation Proclamation, but was quickly drowned out by shouting and a “scene … wild and grand.” In the next hour Douglass hugged perhaps more people than he had before in his entire life, some of whom were old enemies. That night there were no Garrisonian or anti-Garrisonian tears. An old preacher named Rue stood front and center with Douglass as they led the assembled in the anthem “Blow Ye the Trumpet, Blow” and repeated the verse “Sound the loud timbrel o’er Egypt’s dark sea, / Jehovah hath triumphed, his people are free.” (Blight, 383)

"Early the next morning Garrison rushed to The Liberator’s office. The proclamation was better than expected. It did more than free the confiscated slaves of rebels; it emancipated all the slaves in the rebel states. Not only would the nation regard all those people as free, but it would extend military protection to them and accept their enlistment “in the armed service of the United States.” … Lincoln’s eloquence flared momentarily in the concluding lines describing the decree as “an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity” for which he asked “the considerate judgement of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.” (Mayer 547)

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blight, D. W. (2018). Frederick Douglass. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Mayer, H. (1998). All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation/transcript.html